BY JED GRAHAM

INVESTOR’S BUSINESS DAILY

Posted 9/30/2005

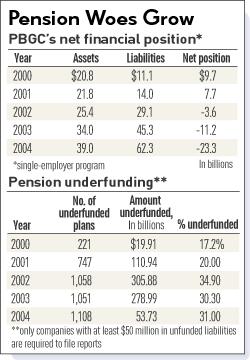

The Pension Benefit Guarantee Corp., the government agency that insures private pensions, already had a $23 billion deficit before the recent bankruptcies of Delta and Northwest Airlines.

If those companies unload their pension obligations on the government in bankruptcy proceedings, as some observers expect, the PBGC’s deficit could jump as much as 50%.

The problem isn’t just that major steel and airline companies have gone belly-up due to pressure from changing industry economics and more agile competition.

“There’s a serious structural imbalance between the (insurance) premiums that Congress allows the PBGC to charge and the risk that Congress puts on the shoulders of the PBGC,” said Douglas Elliot, president of the nonpartisan Center on Federal Financial Institutions.

Legislation moving through Congress this fall is geared toward creating a better balance between the risk that the PBGC bears and the premiums paid by companies with defined-benefit pension plans.

The good news is that the legislation, if passed, should eventually cut the PBGC’s long-term funding hole roughly in half, Elliot says. The bad news is that the PBGC’s finances will still get worse in the medium term.

Without reform, Elliot figures it would cost $92 billion in today’s dollars to keep the PBGC solvent in the long term. Even with reform, the PBGC is still likely to need a taxpayer bailout of $40 billion to $50 billion, he says.

The Congressional Budget Office, in its analysis of the House version, also found that bill would do little to keep the PBGC deficit from getting bigger near-term:

“The bill would lead to an increase in underfunding among plans that would be terminated over the next decade, thus increasing outlays by the PBGC for pension benefits,” the CBO wrote.

While differences in the House and Senate bills, which are expected to pass in coming weeks, will have to be ironed out, they share much in common.

Both would raise the premium for single-employer pension plans to $30 per person from $19 per person and index it to wage growth. The per-person premium hasn’t been raised in more than a decade.

The current premium generates about $650 million per year. The increase will raise PBGC revenue by $4.9 billion over the next decade, CBO estimates.

In addition, companies are required to pay a premium of $9 for each $1,000 by which the plan is underfunded. Proposals before Congress would tighten the rules that have let companies avoid this additional expense.

To fully offset the estimated $86.7 billion in exposure the PBGC faces over the next decade would require Congress to raise premiums by a factor of 6.5, CBO says. But Congress, which is opting for a much more modest adjustment, faces a delicate task in raising the costs for companies with defined-benefit pensions.

First, companies already in weak financial straits won’t be able to handle a significantly higher burden. That’s why Congress is making a special exception for Delta and Northwest, which have asked for up to 25 years to make up their funding shortfalls. The latest Senate version would grant them a 14-year reprieve.

If Delta and Northwest terminate their pension plans in bankruptcy, the PBGC would have to make good on $8.4 billion of the shortfall in Delta’s plans and another $2.8 billion in claims related to Northwest.

The PBGC already assumed $6.6 billion of United Airlines’ $9.8 billion pension shortfall, with United employees taking a $3.2 billion hit in lost benefits.

Underfunded Pensions Swell

The PBGC says that the total amount by which corporate defined-benefit pensions are underfunded reached $450 billion in 2004. About $96 billion of that underfunding, which represents a potential loss to the PBGC, is from junk-rated companies, such as GM and Ford.

But much of the underfunding comes from financially fit firms. If Congress raises insurance rates too much, companies might be disposed to drop their defined-benefit plans.

“It is important to remember that private DB plans are voluntary,” Goldman Sachs noted in a research report on pension reform.

While companies with plans covered by collective bargaining agreements wouldn’t be able to exit the system unilaterally, others would, Goldman noted. And if healthy companies leave the system, the PBGC will grow more dependent on premiums from financially weak companies.

Defined-contribution plans such as 401(k)s have become increasingly popular. Few, if any, companies launch defined-benefit plans anymore. But while the number of single-employer plans covered by PBGC has shrunk from 95,000 in 1980 to 30,000, the number of covered employees and retirees has grown to 34 million from 27.5 million.

Companies have opted for the defined-contribution plans because costs are more predictable, administrative costs are lower and employees, who are more likely to have multiple employers, prefer the portability, Goldman notes.

But Goldman rejects the notion that the defined-benefit pension system, which transfers risk to employers and provides benefits for life, “is structurally flawed or beyond repair.”

Still, the pension insurance system clearly needs fixing. PBGC executive director Bradley Belt didn’t sugarcoat the situation in recent testimony before Congress: “The system is not viable as it stands. On the other hand, with reform, we have a good chance of revitalizing the system.”